The non-linear world of B2B buying

August 28, 2018

It’s falsely comforting to think of selling as a process in which one step follows logically after another. But although rigidly defined processes might be the best way of running a manufacturing production line, they fail to reflect the reality of any moderately complicated sales environment.

It’s falsely comforting to think of selling as a process in which one step follows logically after another. But although rigidly defined processes might be the best way of running a manufacturing production line, they fail to reflect the reality of any moderately complicated sales environment.

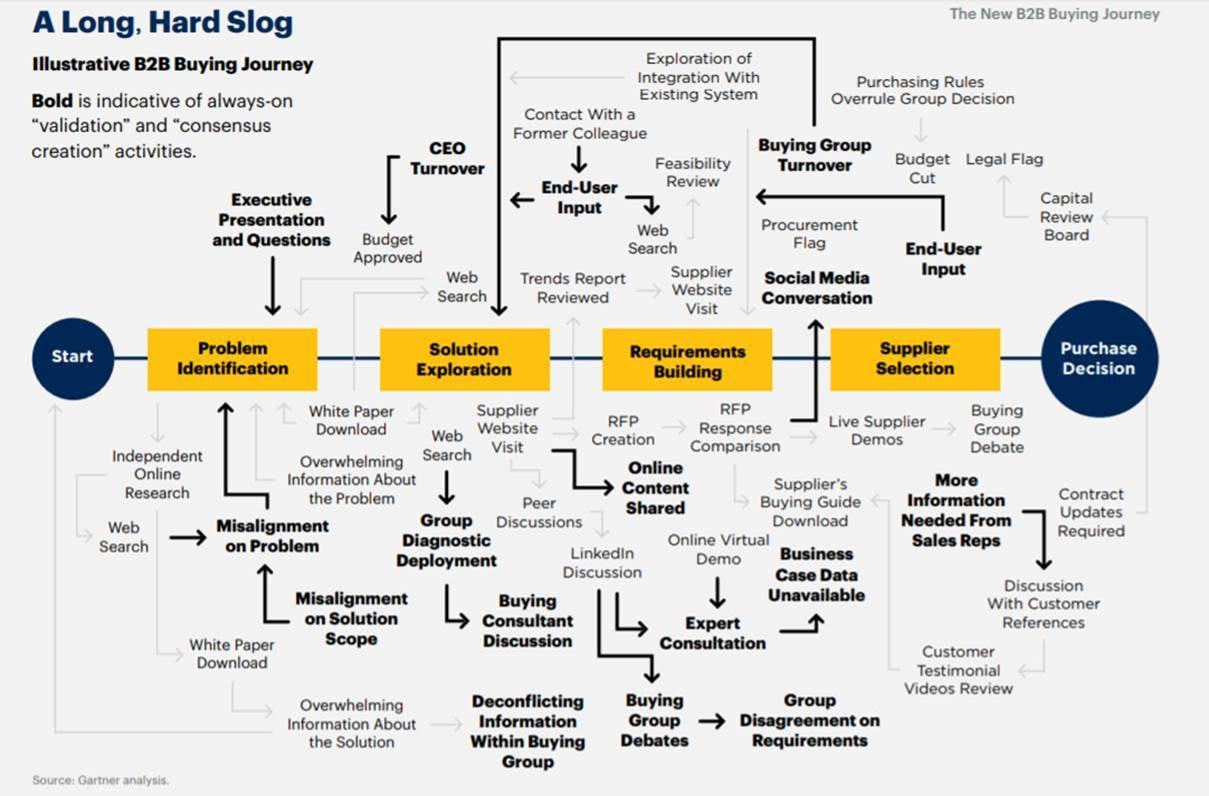

It would be convenient if things were simpler. But the brutal truth of the matter is that in complex B2B sales our customer’s buying processes are rarely linear, compounded by the fact that they are sometimes poorly defined and even if they appear to be well defined are not always well understood by the customer themselves [by the way, you can click on the above image to see a larger version].

Rather following a hypothetically straight path, many customer decision journeys zig and zag, go backwards as well as forwards, find themselves way off-piste, struggle to achieve consensus, can be redirected at the behest of a single powerful individual and can be abandoned at any stage along the way...

And then there’s the opposite effect when - typically during a formal procurement process following the issue of an RFP - when the whole system might have the appearance of being in lockdown with very tightly controlled vendor interaction, even if the reality is otherwise.

The convoluted nature of the typical situation is nicely represented (and quite possibly under-estimated) in the above diagram from Gartner. It’s no wonder that so many complex B2B sales opportunities fail to make the progress that the sales person sometimes naively expects or hopes for.

No magic wand

There is no magic wand, but there are a few things we can do. The first is to accept that for any significant purchases, our customer’s decision-making journeys are inherently complex. The second is to accept that we will probably never achieve anything close to perfect knowledge.

But we can do our best to avoid being blind-sided by factors that we ought to be able to predict are likely to come into play. Rather than following a rigid, linear “sales process”, we firstly need to diagnose where our customer is in their decision journey.

As we’ve learned, this can change at any time and without notice. Some members of the decision group may be ahead of the curve, and some behind. It’s particularly important that we aren’t deceived by an over-enthusiastic champion into thinking that the group as a whole are further advanced than they really are.

The decision journey

Broadly speaking, the current centre of gravity of the customer’s decision journey is likely to be in one of the following phases:

Unconcerned: The customer, by and large, is currently unconcerned about any of the issues we might be targeting and is not yet engaged in any form of active buying decision journey.

Exploring: Something has happened to draw the customer’s attention to one of these issues, and they are trying to establish the potential impact of the issue, what remedies might be available, and whether there might be a business reason to act.

Defining: Having agreed that the issue probably requires action, the customer now turns their attention to identifying potential options, and defining their decision criteria, decision team and timeframe.

Selecting: The customer is evaluating the pros-and-cons of their shortlisted options, further refines the business case and seeking to identify their preferred option (which may end up being “do nothing”).

Verifying: The customer is seeking to verify their choice, to negotiate the best possible terms, to eliminate any remaining reservations and to secure the support of their colleagues for the project.

Confirming: The project and its associated business justification is submitted to the ultimate decision authority for final approval - and often finds itself competing for funds with other investment opportunities.

These descriptions are somewhat idealised. It is entirely possible that some projects rush through or skip some of these phases altogether. As we’ve acknowledged, the journey can stall, go into reverse or go forwards. But it appears that when key phases are not completed to at least a minimum level - for example, clearly defining the needs and process - that it is far more likely that the journey will subsequently fail.

Events that might throw the journey into reverse could include:

- A new and powerful stakeholder re-examining some of the previous decisions of the stakeholder group

- A persuasive sales person convincing the stakeholder group that they need to revisit their decision criteria

- The emergence of another competing project that is seen to be of more urgent importance

We can’t know here the customer is on their journey unless we observe their behaviour closely for the relevant indicators. And we can’t assume that their next step will be forwards. But we can facilitate that movement by eliminating anything which is under our control or influence that could otherwise hold them back. We might even create value (and influence the outcome) by suggesting things that should be part of their decision journey.

Stakeholder engagement

The other key factor is the involvement and attitude of key stakeholders. As the authors of “The Challenger Customer” pointed out, consensus is often hard to achieve, and is one of the primary reasons why apparently promising projects end up going nowhere.

It’s probably unrealistic to expect that we can directly identify, engage and persuade all the stakeholders in a complex buying decision. But we need to do our best to recognise who and what we don’t know and take steps to improve our knowledge of and engagement with them.

The more we know about these stakeholders’ role in the process, their level of influence, their attitude towards us, their motivations, priorities and personal decision criteria, the better.

But even if we have engaged some of these other stakeholders, we’ll often find ourselves relying on a particular champion to promote the virtues of our solution to their colleagues - so we had better assess whether they have the necessary qualities to act as the “mobiliser” or change agent.

Even if they are not the ultimate decision authority (it’s obviously better if they are) , effective change agents need to have the reputation, ability and personal influence to be able to navigate the organisational politics and persuade their colleagues to align behind their preferred solution.

If we cannot be confident that our apparent champion has these attributes, we need to review our strategy and - probably - revise our level of confidence that we will end up winning the deal.

The dangers of over simplification

In this, and in all other matters, we will end up making better choices and securing better outcomes if we recognise that the environment into which we have to sell is complicated, non-linear, sometimes unknowable and rarely predictable rather than fooling ourselves into thinking that our world can be encapsulated in a simple model.

Please share your thoughts on these ideas - do they match your experience?

This article was first published on LinkedIn.

IF YOU ENJOYED THIS ARTICLE, YOU'LL PROBABLY ALSO APPRECIATE:

READ: Introducing the Value Selling System

READ: In complex B2B sales, stakeholders have more than one dimension

DOWNLOAD: The Essential Principles of Value Selling

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Bob Apollo is a Fellow of the Association of Professional Sales, an award-winning blogger, a confident and entertaining event speaker and workshop leader, a regular contributor to the International Journal of Sales Transformation and the founder of UK-based Inflexion-Point Strategy Partners, the B2B value selling experts.

Bob Apollo is a Fellow of the Association of Professional Sales, an award-winning blogger, a confident and entertaining event speaker and workshop leader, a regular contributor to the International Journal of Sales Transformation and the founder of UK-based Inflexion-Point Strategy Partners, the B2B value selling experts.

Following a successful career spanning start-ups, scale-ups and corporates Bob now works as an adviser to some of today’s most ambitious B2B-focused sales organisations, equipping and enabling them to accelerate revenue growth and transform sales effectiveness by implementing the proven principles of value selling.

Comments